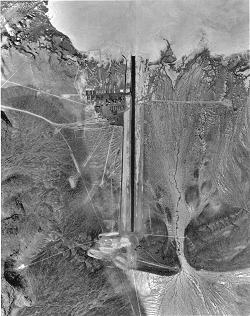

This aerial view shows the Watertown Airstrip at Groom Lake in 1959. The paved runway is 5,000 feet long.

This aerial view shows the Watertown Airstrip at Groom Lake in 1959. The paved runway is 5,000 feet long. |

There would also be times when the Sheahan family and the miners would have to evacuate. The days of non-productivity were a costly nuisance to the Sheahans. The frequent nuclear testing required the mine "to be shut down often, once as long as 12 days in a row," according to Fuller. As Fuller describes the fallout from interviews with surviving Sheahan family members, it "would just sweep in, thick as a dry thunder shower, just as heavy and just as pelting as actual rain." Cattle, horses, and deer in the Groom area were later observed dead or injured with beta burns, a form of radiation damage from fallout.

Other damage at the Groom mine was caused by shockwaves from the blasts. One detonation broke 30 windows and ripped sheet metal off the sides of buildings. According to Fuller, the Sheahans were informed that detonations were planned for times when the winds would send the atomic clouds north and east. In this way, the fallout would pass over sparsely populated areas, rather than major cities like Las Vegas, Nevada, and Los Angeles, California. In later years, this necessity would plague the workers at the secret Groom Lake airfield with the need to suspend operations and evacuate personnel during nuclear tests.

The airfield at Watertown, on the southwest corner of Groom Lake, as it appeared during the 1950s. U-2 aircraft were parked north of the hangars and west of the runway. |

An information booklet distributed to the news media in 1957 by the AEC (titled Background Information On Nevada Nuclear Tests) mentioned the "Watertown Project." It was described as "a small facility at Groom Dry Lake adjacent to the northeast corner of the Nevada Test Site, and within the boundaries of the Las Vegas Bombing and Gunnery Range." It noted that the base included "dormitories, equipment, buildings, and a small airstrip."

Naturally, there was no mention of the fact that it had been built for the CIA to test fly a new spyplane and train pilots for covert reconnaissance missions. The booklet did include a cover story that the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) had "announced that U-2 jet aircraft with special characteristics for flight at exceptionally high altitudes have been flown from the Watertown strip with logistical and technical support by the Air Weather Service of the U.S. Air Force to make weather observations at heights that cannot be attained by most aircraft." In fact, U-2 aircraft at Waterown were painted in NACA markings to protect the cover story in the event that one of them was lost off-site.

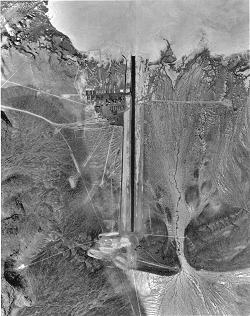

Shot STOKES was fired from a balloon above Area 7. It exploded with a yield of 19 kilotons. The fallout cloud passed through the Groom Lake area. |

A memo from Brig. Gen. Alfred D. Starbird in the Department of Energy (DOE) historical archives describes a teleconference regarding Watertown exposure to fallout during the 1957 test series. According to the memo, the "Watertown agreement requires that personnel evacuate, if necessary, to permit [the] test device to be fired." It was also cautioned that "expected fallout on Watertown from a given shot should be limited so as to permit re-entry of personnel within three to four weeks without danger of exposure exceeding the established off-site rad-safe [radiation safety] criteria, and with understanding that evacuation for a later shot may be required."

It was requested that this position be passed on to the Nevada Test Organization planning board, and that the Board should determine "delays in firing which may result, if any, from Watertown consideration," and "maximum tolerable fallout on Watertown under stated conditions." At this time, the Groom Lake facility was only being used for the U-2, and was expected to be deactivated as the aircraft and crews were dispersed to overseas bases for operational missions. The memo states: "Latest info here indicates Watertown will continue operation through June 30, 1957, and possibly for an additional year thereafter." The evacuations must have been inconvenient to Watertown personnel, as they would have had a severe impact on flight test and training schedules.

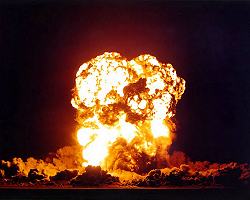

Shot SMOKY was fired atop a steel tower in Area 2, adjacent to some hills. It had a yield of 44 kilotons. SMOKY's dusty cloud deposited radioactive fallout over the Groom Lake area. |

On the morning of 24 April 1957, an XW-25 warhead was subjected to a one-point detonation. Only the bottom detonator was fired. The warhead's high-explosive charge destroyed the weapon and spread plutonium over nearly 900 acres of the surrounding landscape. The primary hazard from plutonium is the danger of inhaling microscopic particles. Alpha radiation emitted by the material is very weak, but can damage soft tissue (as in the lungs).

Ground Zero for Project 57 was only five miles northwest of Groom Dry Lake. Initially, no fallout was detected at Watertown. It was later determined that there was minor alpha activity for 12 days following the shot, but it was well below operational guidelines.

HOOD, the sixth nuclear shot of Plumbbob was truly spectacular, and caused substantial damage at Watertown. The device had been designed by the University of California Radiation Laboratory at Livermore, California. It was lofted by balloon to a height of 1,500-feet over Area 9, about 14 miles southwest of Watertown. At 4:40 a.m. on 5 July 1957, HOOD exploded with a yield of 74 kilotons, the most powerful airburst ever detonated within the continental United States. It was five times as powerful as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, during World War II.

According to Under The Cloud by Richard Miller, HOOD was a thermonuclear explosive, or hydrogen bomb. It was detonated in spite of an informal agreement between the government and the military precluding the use of fusion weapons on U.S. soil. Miller cites a letter from Col. William McGee of the Defense Nuclear Agency, dated 7 July 1980, which admits that HOOD "was a thermonuclear device and a prototype of some thermonuclear weapons currently in the national stockpile."

HOOD's nuclear cloud drifted over Groom Pass and the Papoose Range, depositing fallout on the Watertown camp where the blast had already left its mark. According to a memorandum from R.A. Gilmore of the Nevada Test Organization's Off-Site Radiation Safety Office, HOOD's shockwave damaged a number of buildings at Watertown. Damage included shattered windows on the west sides of Building 2 and the Mess Hall, a broken ventilator panel on the north side of Dormitory Building 102. Two metal Butler buildings suffered the most severe blast effects. A maintenance building on the west side of the base had its west and east doors buckled, and the south door of the supply warehouse west of the hangars buckled in.

A warehouse west of the Watertown trailers experienced a maximum of 75mR/hr inside, while levels outside the building reached 110mR/hr. The Base Theater received 90mR/hr for a few minutes as the cloud passed. Levels inside the cab of the Control Tower reached 37mR/hr, while outside levels were up to 60mR/hr. Additional readings were taken in several types of office and storage buildings, and even on the Volleyball court.

Measurements were also taken inside parked vehicles positioned on Groom Lake Road. Radiation monitoring equipment was placed inside trucks, some with closed windows and some open. One truck (with windows open) was located 9.5 miles west of Watertown, along Groom Lake Road. This turned out to be a real "hot spot." The interior of the metal cab received 950mR/hr, while outside registered 1,420mR/hr (or 1.42R). Another truck, two miles west of Watertown only received 0.3mR/hr inside the cab and 0.5mR/hr outside.

The OXCART program operated at Area 51 from 1962 until 1968. This did not signal the demise of the remote airbase, however. Other CIA and Air Force programs sustained it for many decades. The Air Force took control of the site in 1977, and it has only continued to grow.

Fallout and debris from cratering shots were hurled high into the atmosphere. The first cratering test was actually sponsored by the Department of Defense, and was not part of Plowshare. Called DANNY BOY, the 0.43-kiloton shot blasted an 84-foot deep, 265-foot wide crater in basaltic rock on 5 March 1962. Radioactivity was detected off-site, probably at Area 51 which was downwind. The largest cratering shot was SEDAN, on 6 July 1962. The 104-kiloton thermonuclear device left a crater 1,280 feet across and 320 feet deep. Again radioactivity was detected off-site. Shot ANACOSTIA was a low-yield device development test on 27 November 1962. No radioactivity was detected beyond the boundaries of the Test Site.

Two other Plowshare cratering tests were scheduled for 1969. The shots, code named YAWL and STURTEVANT, were planned for detonation on northern Yucca Flat. In preparation for the tests, DOE officials analyzed the predicted effects that the blasts would have on Area 51. Documents titled EVENT SAFETY AND DAMAGE EVALUATION - AREA 51 for each test are available at the DOE Public Reading Facility in Las Vegas. These draft reports provide insight into the manner in which nuclear testing impacted operations at Area 51. The analyses for both shots cover the following areas: predicted effects, atmospheric overpressures, radiation, base surge and ejecta, possible damage to Groom Lake road, evacuation from Area 51, and possible delays in firing.

According to the documents, the STURTEVANT device was to be buried about 800 feet below ground, and have a yield of 170 to 250 kilotons. YAWL was to have a yield of 750 to 900 kilotons. Buried about 1,000 feet underground, YAWL would have blasted a crater 500 to 700 feet deep and as much as 1,500 feet across. Predicted effects of both shots were similar. "Anticipated ground motion at Area 51 Camp," according to the STURTEVANT report, "is below the damage threshold for structures, therefore, only minimal architectural damage is expected."

Radiation was an important consideration. Neither shot would have been fired if winds would cause the "hot line", area of highest radiation, to pass near the airbase. The reports state that "wind conditions at detonation time will be chosen such that predicted contamination at Area 51 camp will be less than 6R total dose including shine and redistribution. The dose rate is expected to fall below 6mR/hr before D+4." To reduce risk of radiation exposure, personnel were to be evacuated as with so many previous shots. "Detonation...will require evacuation of the entire Area 51 on D-day." Additionally, the duration of the evacuation would "depend on reliability of contamination predictions and in-field measurements. Re-occupancy is expected by D+4 although field conditions may require short work shifts for several days, possibly two to three weeks."

The possibility of successive firing delays raised the specter of evacuation for a period of days, or even weeks. As always, weather was the determining factor. The reports specified that it might "be necessary to delay detonation on a day-to-day basis awaiting favorable atmospheric conditions." In the case of YAWL and STURTEVANT, all the planning was in vain. Both shots were cancelled.

The proximity of Watertown/Area 51 to the Nevada Test Site helped shield activities at the airstrip under the blanket of security that already surrounded the nuclear proving ground. It also created such operational difficulties as radiation exposure, damage to facilities and equipment, and numerous delays due to evacuation. Air Force, CIA, and civilian contractor personnel at the secret airbase willingly accepted these risks in order to accomplish their mission: to develop advanced aircraft and systems in defense of the United States.